Video

Design and Construction

Architect and Construction Firm

The Central Building of the Executive Yuan was designed by Ide Kaoru, an architect from the department of construction at the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan. After graduating from Tokyo Imperial University in 1906, he moved to Taiwan in 1911 and stayed 34 years.

Among Ide’s well-known works are the Jinan Presbyterian Church (1916), the former American Cultural Center (1931, originally the Taiwan Education Association Building), the Judicial Yuan building (1934), Taipei Zhongshan Hall (1936, originally Taipei City Public Auditorium), the old library building of National Taiwan University (1928), the College of Liberal Arts of National Taiwan University (1928) and National Taiwan Normal University’s assembly hall (1929).

Which contractor built the Central Building? The structure, which originally housed the Taipei Municipal Office, was a source of local pride as it was built by the Hsieh-Chih Association, a Taiwanese construction firm that later became an electrical and metal factory for motors, fans and refrigerators under the brand Tatung Company.Hsieh-Chih earned the right to build the Taipei Municipal Office because of outstanding work earlier on the Postal Department building (1925) behind the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan.

The Taipei Municipal Office took three years and four months to complete. The overall site area covered 24,598 square meters, and the four-story building with a partial basement had floor space totaling 11,144 square meters.

Central Building as a National Historic Site

- Location

- The building sits on the site of the former Huashan Elementary School, which during the Japanese colonial era was the largest primary school in Taipei in terms of land area.

- The Japanese administration intended the Taipei Municipal Office to be the geographical heart of its colonialist rule. This is the site from where the city expanded outward. This type of spatial planning is markedly different from how the previous Qing dynasty laid out the city’s streets.

- After World War II, the building successively housed the highest administrative organs in the land: the Office of the Taiwan Provincial Administration, the Taiwan Provincial Government and now the Executive Yuan.

- National Historic Site Designation

On July 30, 1998, the Ministry of the Interior designated the Central Building of the Executive Yuan a national historic site for the following reasons:- During Japanese rule, the building was the site of the Taipei Municipal Office. After Taiwan was restored to ROC rule, the building served as the premises for the Office of the Taiwan Provincial Administration, the Taiwan Provincial Government and the Executive Yuan.

- The structure is an important example of modernist architecture from the late Japanese colonial era.

- Architectural Design

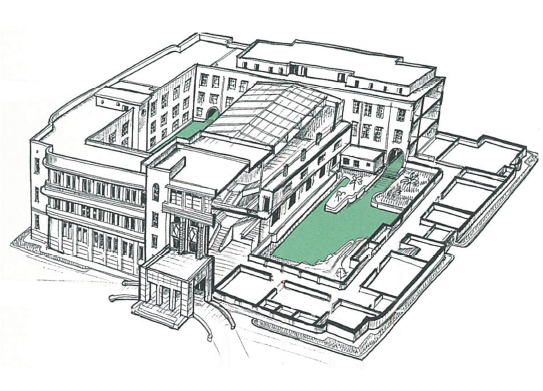

With each floor covering over 3,300 square meters, the Central Building of Executive Yuan was one of few large government buildings constructed during the late Japanese colonial era. In those days, the structure was at the forefront of modernist architecture, built in the shape of a squared-off figure “8” with offices along the four sides and meeting venues at the center. The section above the main entrance rises to four stories while the remaining areas are three stories tall. Although the symmetrical façade is classical in design, the style is quite novel. At the main entrance stand a pair of square columns topped with unadorned capitals. The inside of the building is lined with corridors and the outside with protruding balconies. All balcony corners are curved for a horizontal streamline style, which is common among the modernist architecture of the 1930s. Except for the white columns and original portico, the exterior wall is covered in brown tiles, dubbed “defense color tiles” as they provided camouflage against air raids. Rather than a triangular pediment, a round dome or a tall steeple, the structure is topped with a flat roof. Other horizontal lines are emphasized on the exterior as well as in the interior. This shows a strong influence from the modernist movement that was popular during the peak of Japanese expansion when the Central Building was constructed (1937).

Ten Architectural Features of the Central Building

- The architectural design as a whole reflects a 1930s world trend that was influenced by functionalism, as espoused by the Bauhaus School in Germany. The interior space is clearly divided according to function while the exterior design is a combination of simple squares and horizontal lines.

- The symmetric structure forms a squared-off figure “8” shape that surrounds two courtyards. The balanced arrangement of the hallways and stairways on each floor facilitates easy entry and exit by personnel.

- Balconies were constructed on the east, south and west sides as shields from sun and rain. Though the building has since been equipped with indoor air conditioning, the balconies still help conserve energy in Taiwan’s hot climate.

- The balconies and parapet wall surfaces are rounded at the corners. The flowing lines and simple design of the smooth exterior reveal the streamline style favored by expressionism. The strong contrast generated by the horizontal balconies and railings and the vertical giant columns at the central entrance is one of the features of 1930s modernist architecture.

- The simple round columns were built without caps, reflecting the strength of steel-reinforced concrete. The two square columns above the main entrance were decked with simple horizontal ridges for a more prominent texture that accentuates the entrance’s image. These square columns and horizontal lines reveal the influence of the American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

- The exterior walls were covered with brown ceramic tiles, known at the time as “defense color tiles” because they provided camouflage against air raids. The wall has since been repainted in a lighter color that retains a stately, coordinated appearance overall.

- The rooftop being flat rather than pedimented represents a shift in style from eclecticism to modernism, a style that is more progressive than that of Taipei Zhongshan Hall. The wall above the central entrance is covered in a spiraling diamond design. Atop each of the north and south entrances are a pair of ridged columns that reveal the influence of art deco.

- A grand conference room is located on the second floor at the heart of the complex. Improved construction techniques at the time enable the room’s steel trusses to stretch 24 meters across. The building was designed by Ide Kaoru of the department of construction at the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan, an architect who also designed the Taipei City Public Auditorium (now Taipei Zhongshan Hall).

- The interior walls are covered with terrazzo polished in different colors, forming decorative horizontal bands. These were finished by the precast method and executed with fine craftsmanship. The terrazzo material was made from Hanshui and Qili stone produced in Yilan.

- The stairway railings are simple and unadorned, a style popular in the late 1930s. Unlike in conventional buildings, the stairways are located not at the corners but at the midpoints of the four sides. They were built with steel-reinforced concrete for greater seismic resistance.

Huashan Elementary School

The district in which the Executive Yuan now sits was originally named Huashan, or “Kabayama” in Japanese, after Kabayama Sukenori, the first Japanese governor-general of Taiwan. In the early colonial days, this district was set aside for use by the Fourth Elementary School, succeeded by the Chengbei Elementary School and then Huashan Elementary School in 1911.

During Japanese rule, national schools were categorized as elementary schools, public schools or educational institutions—the first two types under the jurisdiction of the education bureau and the third under the police bureau. The three systems had different curricula, buildings and facilities. Elementary schools accepted mostly Japanese students while the Taiwanese children attended public schools.

Huashan Elementary School was laid out like a military base with an outdoor drill area and several classroom buildings. Twenty meters to the front of the main building was a smaller two-story red-brick structure that originally housed classrooms and later became the first home of the ROC Government Information Office. The building was demolished in the 1970s.

- Taipei Municipal Office (1940-1945)

On July 30, 1920, the Japanese governor-general of Taiwan declared an administrative division system for the island that would take effect October 1, 1920. On August 10 that year, the office also announced the locations and jurisdictions of the various prefectures, cities and districts. Taipei City was incorporated under Taipei Prefecture, and the Taipei Municipal Office was established September 1, 1920. According to colonialist records published in 1931, Taipei City covered 41.7177 square kilometers at the time with a population of 244,244.

Taipei Prefecture comprised the nine districts of Qixing, Tamsui, Keelung, Yilan, Luodong, Suao, Wenshan, Haishan and Xinzhuang, covering today’s Taipei City, New Taipei City, Yilan County and part of Taoyuan City. The Taipei Prefecture government operated in what is today the Control Yuan building.

The Taipei Municipal Office was the administrative center of the city. In the beginning, it borrowed space from the Huashan Elementary School and hung the sign “Taipei Municipal Office” at the school entrance.

The office gradually expanded to meet Taipei’s increasing administrative needs. Starting with only the general affairs and financial affairs sections in 1920, the organization by 1941 swelled to 17 sections: documents, accounting, general affairs, industrial development, military affairs, defense, tax affairs, academic affairs, social education, social welfare, business development, agriculture, civil engineering, public works, public health, water works and transportation.

In total, Taipei City saw 12 mayors under Japanese rule. Taketohari Goro was the first and longest-serving mayor at four years and three months. Construction of the city office building ran from 1937 through 1940, and the city government operated in the new building thereafter, under mayors Ishii Ryucho and Kihara Enji.- Origins of Taipei Municipal Office

In the early days of colonialism, Taipei had no mayor as it was under direct jurisdiction of the Japanese governor-general of Taiwan. The mayorship was not established until 1920 when Taipei was upgraded to a city and the Taipei Municipal Office created. Taketohari Goro served as the inaugural mayor.

The new Taipei Municipal Office comprised many sections including documents, accounting, general affairs, industrial development, military affairs, defense, tax affairs, academic affairs, social education and business development. It originally operated on the campus of Huashan Elementary School, but as needs expanded, construction began in 1937 on a new office building that would become today’s Executive Yuan Central Building. - Site Selection

Taipei’s most flourishing district during the Qing dynasty was Mengjia (now Wanhua), and later Dadaocheng following conflicts between Fujian and Guangdong immigrants and the opening of Tamsui Port. After Imperial Commissioner Shen Bao-zhen received permission in 1875 to establish Taipei Prefecture in northern Taiwan, builders hired by the Taiwan provincial government began constructing a walled city in 1882 and completed the Taipei Prefecture capital in 1884.

The Executive Yuan now spans Zhongxiao East Road, Zhongshan North Road, Beiping East Road and Tianjin Street, but this bustling area was bare of buildings back in the Qing dynasty. Located outside the northeast limits of the Taipei Prefecture capital, the area was part of Sanbanqiao (Dazhuwei) district, which was covered by ditches and water fields at the time. Nearby was the Taiwan railways headquarters, established by Taiwan’s first Qing governor, Liu Ming-chuan.

After Japan took control of Taiwan in 1895, the colonialists implemented their own urban plans for Taipei and demolished the city walls. In 1904, the colonial government built a three-lane road (now Zhongshan South Road), an imperial envoy road linking Yuanshan Shrine (now the Grand Hotel Taipei), and a three-lane road to Keelung running eastward from Taipei Railway Station (now Zhongxiao East Road). It also designated space inside and east of the city for public buildings, government agencies and schools.

The Japanese administration’s plans for public buildings in Taipei were implemented over several stages. In the early 1900s, work began with demolition of the city wall. The colonialists then focused on the city’s central and eastern parts and built Taipei Station (1900, now Taipei Railway Station), the Japanese governor-general’s residence (1900, now Taipei Guest House), Taipei Post Office (1919, corner of today’s Boai Road), the Bank of Taiwan (1938) and local courthouses. Urban re-zoning plans were also implemented.

After 1911, the colonialists took to constructing government buildings, including the Central Research Institute of the Governor-General’s Office (1911, now a United Daily News office building), Taipei Prefecture Hall (1915, Control Yuan), a military command headquarters (Coast Guard Administration), the Governor-General Museum (1915, National Taiwan Museum), the Monopoly Bureau (1916, Taiwan Tobacco and Wine Monopoly Bureau), the Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan (1919, Office of the President), the New Park (228 Peace Memorial Park) and Taipei Municipal Office (1937, Executive Yuan Central Building).

The site for the Taipei Municipal Office was determined in the second phase of urban planning. The building was completed in 1940 and the city administrators moved in in 1941. Two mayors, Ishii Ryucho and Kihara Enji, served in this building.

- Origins of Taipei Municipal Office

- Office of the Taiwan Provincial Administration (1945-1947)

After Japan’s surrender to the Allies on August 14, 1945, the Nationalist government appointed Chen Yi as chief executive of Taiwan Province on August 29. On September 20, the government announced an organizational framework for the Office of the Taiwan Provincial Administration under the Executive Yuan. The office took over local administration duties and designed the local government structure. It operated in the original Taipei Municipal Office building. - Taiwan Provincial Government Office (1947-1957)

In 1947 following the February 28 Incident, the Office of the Taiwan Provincial Administration was dissolved on May 16 and replaced by the Taiwan Provincial Government. Five chairmen of the provincial government served in this building: Wei Tao-ming, Chen Cheng, Wu Kuo-chen, Yu Hung-chun and Yen Chia-kan.

On June 30, 1957, the Taiwan Provincial Government relocated to Nantou County in central Taiwan, and the building then passed hands to the Executive Yuan. - Executive Yuan (1957-Present)

Since the Taiwan Provincial Government moved to Nantou in 1957, the Central Building has been home to the Executive Yuan. As of 2014, a total of 18 premiers have served in the building: Chen Cheng, Yen Chia-kan, Chiang Ching-kuo, Sun Yun-suan, Yu Kuo-hwa, Lee Huan, Hau Pei-tsun, Lien Chan, Vincent Siew, Tang Fei, Chang Chun-hsiung, Yu Shyi-kun, Frank Hsieh, Su Tseng-chang, Liu Chao-shiuan, Wu Den-yih, Sean Chen and Jiang Yi-huah.

Ten Attractions

Front facade

The Central Building was built from 1937 to 1940 by the Japanese colonial government. Its style differs from the late-Renaissance style seen in the Control Yuan building (1915, originally Taipei Prefecture Hall), Taiwan Tobacco and Wine Monopoly Bureau building (1922, originally Taiwan Provincial Monopoly Bureau building), Office of the President (1919, originally Office of the Governor-General of Taiwan), and the original building of National Taiwan University Hospital (1916).

Rather than a triangular pediment, a round dome or a tall steeple, the building is topped with a flat roof. This shows a strong influence from the modernist movement that was popular during the peak of Japanese expansion when the structure was constructed (1937). The exterior puts a strong emphasis on clean blocks and horizontal lines, the same style used for Taipei Zhongshan Hall (1936, originally Taipei City Public Auditorium).

Though the Central Building has the appearance of a three-story structure, it actually has four stories rising 16.5 meters total. According to construction records, the floor space of the first to fourth floors measure 3,709 square meters, 3,461 square meters, 3,200 square meters and 774 square meters, respectively. It was constructed from 1937 to 1940 originally to accommodate the Taipei Municipal Office. Well preserved and still in use, this is a fine example of a government building from the Japanese colonial period.

Entrance lobby

In the 1930s, the art deco style swept the design world with its emphasis on decorative art. In those days, many design themes were characterized by bold geometric shapes and patterns. The diamond grid is one such concept advocated by the famous American architect Frank Lloyd Wright.

In the Central Building entrance lobby, the door panels show the diagonal lines and diamond patterns favored by art deco stylists. At the grand stairway, the handrails are simple and unadorned, another popular style from the late 1930s. The walls were covered with granite panels during recent remodeling.

All transom windows above the doors are fitted with diamond grills. This same theme has been designed into the building’s front and rear doors to create a consistent and coordinated feel.

Door panels

The diamond motif used throughout the building can be seen on the door panels of the premier’s office. The elegant diamond carvings lend an air of classical architecture.

Sash windows

The original wood-frame windows in the corridors are still in use. Made from cypress wood, the double-hung sash windows are rarely seen in Taiwan today. Sash chains on both sides of the windows run over a pulley to a counterweight that keeps the top and bottom windows in place and prevents them from sliding down the tracks. This clever design shows the ingenuity of the builders.

Assembly Hall

The Central Building features unique spatial layouts. Unlike most rectangular buildings of the time, the Central Building has stairways situated not at the four corners but at the midpoints of its four sides. The stairways are also built with steel-reinforced concrete for greater seismic resistance.

Above the Assembly Hall, the ceiling is lined with long steel trusses—the most advanced structures of the time. Restrooms are also located not at the ends but at the middle of the corridors for easy access.

Another distinctive feature is the basement, which was rare among government buildings constructed before 1930. The partial basement was built as an air-raid shelter after the Marco Polo Bridge Incident of 1937, which sparked the Second Sino-Japanese War.

Council Hall

At the heart of the Executive Yuan building is the Council Hall, a grand conference room with an imposing high ceiling. The hall has been renovated several times to meet evolving needs, and much of the original appearance has been altered.

Terrazzo interior walls

The terrazzo technique found in the Central Building was popular among Japanese colonial architecture. The interior walls are covered with terrazzo polished in two different colors, forming decorative horizontal bands.

The exquisite craftsmanship itself is worth looking at: Hanshui and Qili stone from Yilan are first precast into terrazzo tiles then mounted on the walls. The edges match up so precisely that not even a needle can pass through. Even more impressive is that the walls still retain that quality condition today.

Water faucets

In the 1940s, few roads in Taipei were paved, and people walking through dusty streets often needed a place to wash up before going indoors. The Central Building offered water faucets at the north entrance to allow visitors to rinse their hands and freshen up before conducting official business. The same thoughtful design can be seen at the original building of the National Taiwan University Hospital.

Exterior walls

The Central Building resembles a squared-off figure “8” with a central axis that divides the structure into symmetric halves. Within the central axis, the lower level is occupied by the Assembly Hall, while the upper level has a grand conference room that rises two-and-a-half stories tall.

Outside, the base of all exterior walls is made of sturdy, beige granite brought in from Japan. The remaining wall surface is paved with brown ceramic tiles, dubbed “defense color tiles” for their camouflage protection against air raids during World War II.

Yushan Hall

The premier often receives guests and foreign dignitaries in the Yushan Hall located on the first floor of the east wing. Inside the room, 25 seats are arranged along the four walls. The premier is seated in the host’s seat by the main wall. To his right sits the chief guest, followed by other visiting guests in order of importance. To the premier’s left are the accompanying guests, also in order of importance.

East courtyard / West courtyard

The building’s entrances face north and south while the squared-off “8” layout forms two courtyard on the east and west. Both courtyards have arched entryways for vehicles to pass through. In recent years, the courtyards have been remodeled into small gardens with fish ponds and beautiful plants including Taiwan date palms, Madagascar almonds and golden dewdrops.